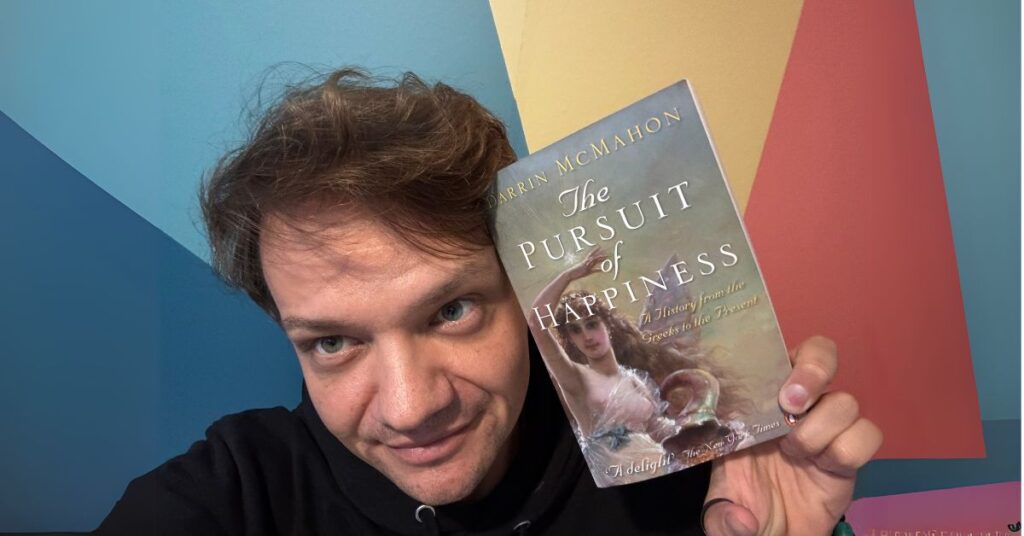

As a happiness author, I decided to review other happiness books, which is why today I re-read The Pursuit of Happiness: A History from the Greeks to the Present by Darrin McMahon.

Honestly, I didn’t like this book as I couldn’t keep my eyes open past chapter 1. However, while it is a negative opinion about this book, can I not express any negative opinions without compromising my self-given title of one of the happiest man alive?

Some people state that I can’t, to which I answer that if I express that positivity is good and we should cultivate more of it in our lives, I also imply that negativity is bad and we should avoid it. Now, can I not express that without being labeled as unhappy? Can I not say that killing is bad by the same logic?

So I didn’t like this book, no big deal. I’m sure there are some people who absolutely loved the book and will recommend it to everyone. Still, let me be a bit more scientific about what I liked and didn’t like.

Specifically, I liked the preface of the book, as it is where I found the most information I appreciated, and part of Chapter 1, as I was still able to read it, without asking myself “is that it?” and “when are we going to talk about happiness?”

In this way, I found the author talking about whatever from whatever perspective he wanted, without saying anything relevant to me. At this point, I was no longer engaged enough to keep reading so I skimmed the rest of the book not finding much later on either.

I believe that partially the problem is that Darrin McMahon is a historian and like most people, he doesn’t have a good definition of happiness to work with, so he goes around speaking about whatever, as technically speaking everything is related to happiness, so where to start or stop talking about this topic?

This is a common problem because in a world where we can correlate happiness with virtually everything, and given the fact that we have a mental health epidemic, something is seriously wrong with society. Most people can’t tell you what happiness is with a strong definition. Thus, if we can’t define happiness, how can we start discussing it? This was exactly my issue with this book.

Nonetheless, there are some things that I liked in this book. For example, I like several quotes the author found, such as:

“The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” – Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

It is interesting to note this quote, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” which implies a certain impossibility of being happy. I recently looked up The Myth of Sisyphus and found that it is a book about contemplating suicide and the absurdity of that notion. Though I haven’t read this book, I understand that it delves into themes of nihilism and existentialism. Personally, I tend to avoid these topics, as I see negativity as merely the absence of positivity, or as Leo Tolstoy wrote:

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

In other words, we can study unhappiness and its many facets almost indefinitely, which we did for the big part of the 20th century. However, in the 21st century, positive psychology and subsequently Optimal Happiness take the stage because we haven’t solved the problem of lack of happiness by simply trying to solve unhappiness. To learn more about this topic, read my book.

Another quote I liked:

“The period of happiness […] are the blank pages of history” – Georg Wilhelm Freidrich Hegel

This quote suggests that we don’t write about history when everything is going right, but we tend to write about the lack of happiness when things are going wrong.

Moreover, as Darrin McMahon correctly pointed out, the word “happiness” in its roots stems from the idea of fortune, luck, and divinity, as for a long part of history, people didn’t feel like they were in control of their fates. It all seemed random, and happiness was reserved for a lucky few who often obtained happiness by the grace of divine providence.

The root of “happiness,” for example, is the Middle English and Old Norse happ, meaning chance, fortune, what happens in the world, giving us such words as “happenstance,” “haphazard,” “hapless,” and “perhaps.” The French bonheur, similarly, derives from bon (good) and the Old French heur (fortune or luck), an etymology that is perfectly consistent with the Middle High German Glück, still the German word for happiness and luck. In Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese, felicità, felicidad, and felicidade all stem from the Latin felix (luck, sometimes fate), and the Greek eudarmonia brings together good fortune and good god. One could multiply these examples at much greater length, but the point would be the same: In the Indo-European language families, happiness has deep roots in the soil of chance.

And

Strictly speaking, luck and fate are opposed, each denies the role of human agency. Whether the universe is predetermined or unfolds chaotically, what happens to us—our happiness-is out of our hands.

Certainly, the majority of history unfolded during a time when people were unable to control their destinies until more or less the Enlightenment period in the 17th and 18th centuries, when the concept of pursuing happiness became a goal we could actively strive for in our lifetimes (even though there is not a consensus on the most efficient way to achieve it).

For example, the Romans believed that happiness lay in pleasure (a viewpoint still held by many today), and thus sought to maximize pleasure through activities such as indulging in excess, accumulating wealth, or engaging in promiscuous behavior.

More recently, Thomas Jefferson included the “right to the pursuit of happiness” as a “self-evident truth” in the Declaration of Independence, while the authors of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789 proposed that the “happiness of all” should be a universal goal, extending happiness to everyone.

Nevertheless, a clear consensus on the definition of happiness and the most effective means of attaining it seems elusive, perhaps contributing to the prevalence of unhappiness in modern society.

“For what did it really mean to demand, and to expect, a lifetime of happiness in a still-imperfect world? Perpetual pleasure? Endless euphoria? Purely material gain? And if human beings had a right to happiness, then did not others have a duty to provide it? To what extent were happiness and freedom commensurate-or happiness and virtue, happiness and reason, happiness and truth? Was happiness simply a state of feeling, the calculus of pleasure and pain? Or did it continue to be a reward, a precious prize to be earned at the cost of sometimes painful sacrifice?”

Luckily, by luck, fortune, or divine grace, I was able to define happiness and become one of the happiest man alive. I don’t say this to boast (I never do, as this would just prove that I’m unhappy), but rather I state it as proof that it is possible for virtually anyone.

We can define happiness from a perspective that is workable and applicable today, so that more people can cultivate it in their lives. Finally, we can apply it to improve the well-being of the masses. While this idea of happiness still seems rather vague, elusive, and even impossible to achieve for most, I believe that today we have all the tools to make a transition towards a utopian future.

To do so, I highly recommend that you familiarize yourself with my work, which is further discussed on this blog, in my book, and on this website.

Stay happy!